Walter Whitman, Acting Librarian

Jeffrey Croteau

New Information About Walt Whitman’s Years as a Printer’s Apprentice and His Involvement with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library in 1835

__

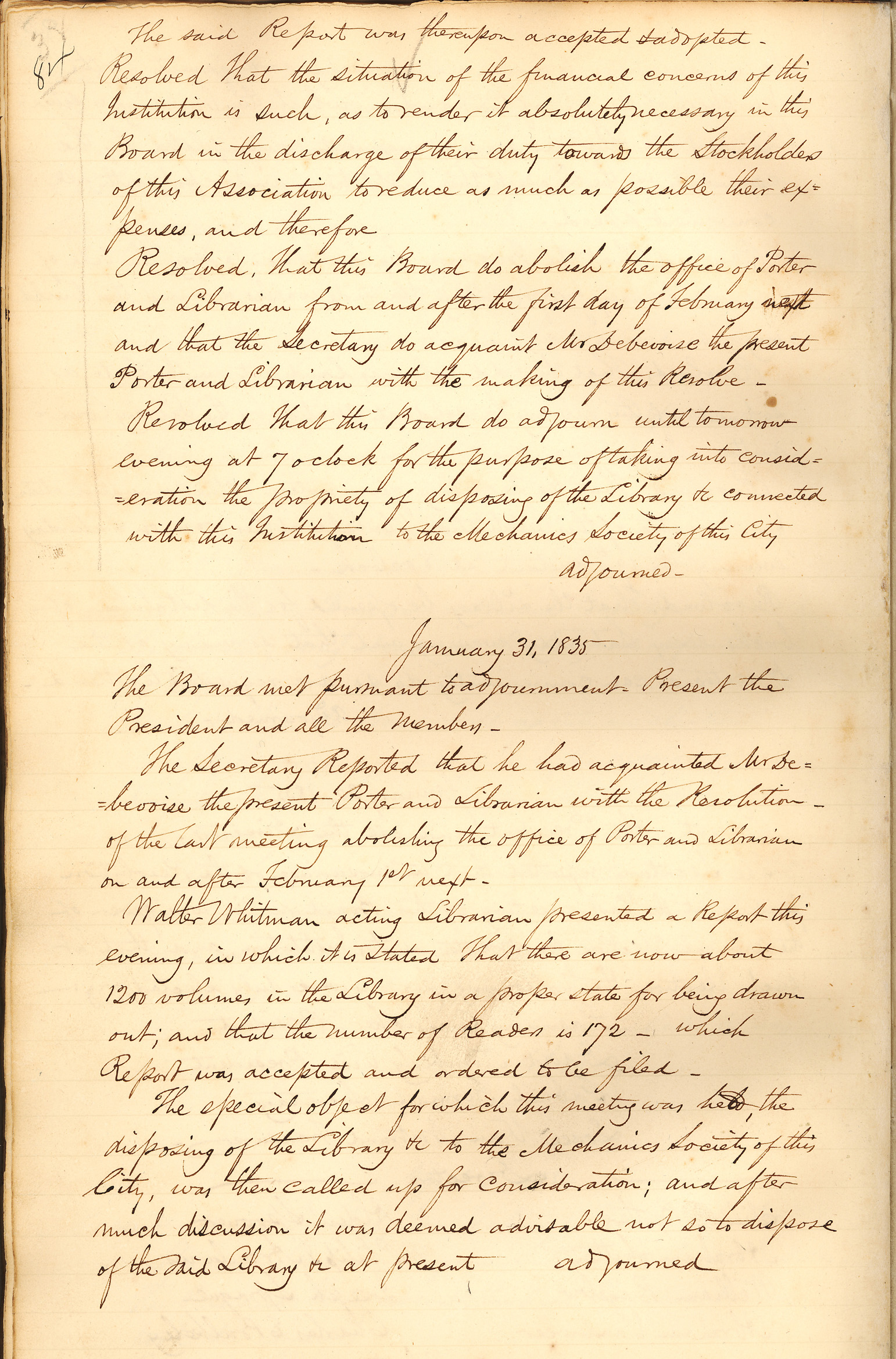

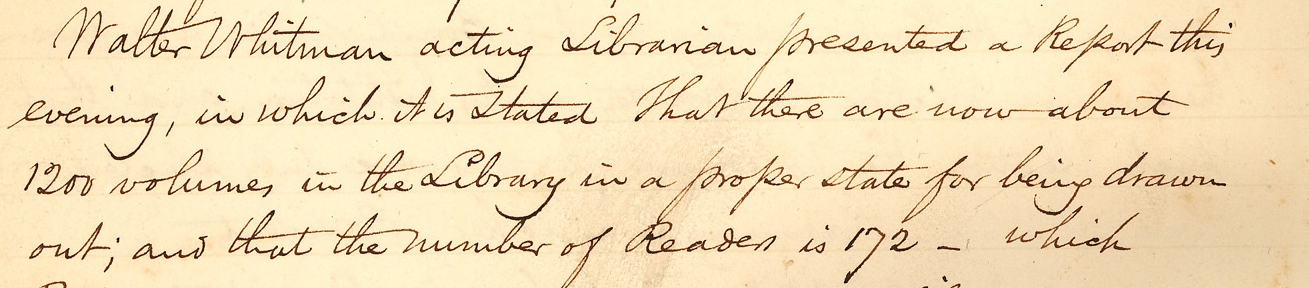

“Walter Whitman acting librarian presented a Report this evening, in which it is stated that there are now about 1200 volumes in the Library in a proper state for being drawn out; and that the number of Readers is 172.” - from an entry in the minutes book of a meeting of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association held on January 31, 1835.

The investigation that follows has its roots in a simple question that has yet to be adequately addressed: did the fifteen-year-old Walt Whitman serve as “acting librarian” for the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library in January of 1835? The question may be new to some, since claims to Whitman’s service at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library have not appeared in Whitman biographies or the scholarly literature.[1] Of the few previous publications that mention Whitman’s service as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, none have investigated this claim. All of the articles that mention Whitman’s service as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library were either published by the Brooklyn Museum or written by someone with a connection to that institution.[2] Claims to Whitman’s librarianship share the same primary source: an entry found in the minutes book of the meeting of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association held on January 31, 1835 which is quoted at the head of this article. The minutes books themselves are in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum’s Libraries & Archives; the Brooklyn Museum traces its history back to the founding of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association - Brooklyn’s first free library - in 1823. To my knowledge, no one has attempted to investigate and further understand what is contained in the entry found in the minutes book or what its implications might be. Therefore, an intriguing question remains: Is the “Walter Whitman acting librarian” mentioned in the minutes book of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association the Walt Whitman?

I was first made aware of the entry in the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association minutes book during the years that I worked at the Brooklyn Museum Libraries & Archives. As I began to explore whether the Whitman mentioned in the minutes books was indeed Walt Whitman, my research led me first on a rather lengthy but important detour into the history of circulating libraries in nineteenth-century Brooklyn. In a recently published article in Library History, I explore the previously unremarked existence of a number of nineteenth-century Brooklyn circulating libraries.[3] That article began as an attempt to simply pursue the few leads that I had and which I thought might eventually help me connect Whitman to the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library. Happily, this pursuit not only led to a broader understanding of the mercantile and social culture in nineteenth-century Brooklyn through its circulating libraries, but it also led - as I had hoped it might - to more conclusive ties between Whitman and the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library.

The two types of libraries discussed in this article – apprentices’ libraries and circulating libraries – were both successful early in the nineteenth century and both began to decline in popularity and number by the mid-nineteenth century. I will briefly define and contrast these two very different types of libraries to help give a better sense of the nature of the libraries that Whitman was both involved with and exposed to during the period covered by this article.

Circulating libraries and apprentices’ libraries co-existed during the early nineteenth century in America because their goals, missions, and clientele were generally mutually exclusive. One could think of apprentices’ libraries primarily as purveyors of education, while circulating libraries primarily as purveyors of entertainment. In most instances, circulating libraries and apprentices libraries were not in competition with each other, in part, because they aimed to serve different clientele with a different selection of books.

Apprentices’ libraries were first established shortly after the economic panic of 1819, a time that left many apprentices without work and, in the eyes of some reformers, dangerously without purpose.[4] William Wood was instrumental in helping to establish apprentices’ libraries starting in 1820, in places as far away and diverse as Boston, New Orleans and Montreal.[5] Apprentices’ libraries were free libraries that were established and then run by a group of older businessmen for the benefit of their apprentice clientele.[6] The book collections reflected the reform-minded mission of these libraries and consisted of texts that would help the reader learn technical skills in the mechanic arts or works that would, it was hoped, direct the young reader to an increasingly moral and civic life. Conspicuously absent from the collections of apprentices’ libraries were novels, plays, and romantic poetry, all of which were viewed by those who founded these libraries to run counter to the mission and goals of an apprentices’ library and, not coincidentally, all of which could be found in abundance in circulating libraries.

Circulating libraries had no high-minded mission and existed as profit-making businesses. The success of circulating libraries during the nineteenth century was partially predicated on the ability to supply what the public wanted to read.[7] And what the public wanted to read was, mostly, novels. Circulating libraries were almost always run in conjunction with another business, usually a bookshop. During the early part of the nineteenth century, printers were often the proprietors of bookshops, and these bookshops also often served as stationery stores as well.[8] It was from these shops that circulating libraries were often, though not exclusively, run. And this is precisely the type of establishment where Whitman worked as an apprentice at three different printing offices in Brooklyn from 1831 until 1835.

The history of circulating libraries in Brooklyn is key to understanding more about Whitman during this lightly documented part of his early life. Circulating libraries provided Whitman’s first exposure to literature; his work as a printer’s apprentice introduced him to the art of printing. The roots of Whitman’s poetic output are generally acknowledged to be found in both circulating libraries and the printing offices where he served as an apprentice[9] and the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass is often seen as the manifestation of Whitman’s dual passion for literature and printing.[10] That is, if it not for Whitman’s introduction to literature at a young age and to the art of printing Whitman may not have ever produced Leaves of Grass, at least as we know it. And, as will be made clear through the course of this article, Whitman was concurrently exposed to literature and printing throughout his years as a printers apprentice, owing to the existence of circulating libraries that were in business in the same buildings as the printing offices in which he worked. Although it is true that Whitman’s first subscription to a circulating library pre-dates his printing apprenticeships, I will show that Whitman’s exposure to literature through Brooklyn’s circulating libraries continued through the entirety of his years as a printer’s apprentice. And it is both through Whitman’s prolonged exposure to the contents of Brooklyn’s circulating libraries as much as it is his exposure to the custodians of those books that would lead to his eventual role as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library in 1835. Like many printers during the same time period, the Brooklyn printers of the 1830s that Whitman apprenticed with also ran a bookstore, a stationery store, and oftentimes, a circulating library from the same building in which they printed books, handbills, and newspapers.

In this brief investigation I will first look at what is known about Whitman during his years as an apprentice in Brooklyn, focusing especially on the years he worked for Alden Spooner who was, among many other things, publisher, editor, and printer of the Long-Island Star. I will then look at what is already known about Whitman’s own statements about circulating libraries in his early life, followed by a closer look at some of the connections that existed between Whitman and specific circulating libraries. Finally, I will look at the waning years of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association, whose dissolution and lack of funding, as I will illustrate, was the probable cause for Whitman’s appointment as acting librarian in 1835.

Walter vs. Walt

The form of the name which is found in the minutes of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library meeting of January 31, 1835 – “Walter Whitman” – brings up a couple of questions that should be addressed at this point. First, if this is the Walt Whitman, why is he referred to as “Walter”? Second, is it possible that there were any other Walter Whitmans living in Brooklyn at the time?

Considering the similarity in name, it is worth briefly considering Whitman’s father, Walter Whitman, Sr., as a possibility, before ruling him out. Walter Whitman, Sr. had already moved (along with the rest of Walt’s family) from Brooklyn back out to Long Island in 1833, and even if he had been in Brooklyn in 1835, he would seem an unlikely candidate to hold such a position, given his trade as a carpenter. With Whitman, Sr. no longer in Brooklyn, we must consider whether there could have been anybody else named Walter Whitman living in Brooklyn at the time. The Brooklyn directories, while not an all-inclusive listing of all of the inhabitants of Brooklyn during a given year, are the best listing of residents we have to work with.[11] Until their departure to Long Island in 1833, Whitman’s family was represented in the directories solely by Walter Whitman, Sr. The final listing for Walter Whitman, Sr. was in the 1833/1834 Brooklyn directory, where he is listed as a carpenter with an address of 120 Front Street; there were no other Whitmans listed in the 1833/1834 Brooklyn directory. No one named Whitman is listed in either the 1834/1835 or 1835/1836 directories, the period during which Walt Whitman was living alone in Brooklyn, the rest of his family having moved back out to the West Hills region of Long Island.

It is unclear whether the directors of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library would have referred to Whitman as “Walt” or “Walter.”[12] However, this may be immaterial, since the minutes are a formal document; the names of the directors are all written out in full. It is reasonable to conclude, that even if the fifteen-year-old Whitman was called “Walt,” that his name would still have been recorded as “Walter” in the minutes.

Finally, despite the case made above, one could entertain the rather remote possibility that another young man named “Walter Whitman” may have lived in Brooklyn at the time and, like the Walt Whitman of this investigation, had not been included in the directory due to his young age and apprentice position, but other factors that point to the “Walter Whitman” of the minutes being Walt Whitman, render this a fairly unlikely possibility.[13]

Whitman and Circulating Libraries

An investigation of Whitman’s eventual appointment as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library must begin in either 1829 or 1830 when, as Whitman himself wrote in Specimen Days (emphasis mine):

At about the same time [i.e. 1829 or 1830] employ’d as a boy in an office, lawyers’, father and two sons, Clarke’s, Fulton street, near Orange. I had a nice desk and window-nook to myself; Edward C. kindly help’d me at my handwriting and composition, and, (the signal event of my life up to that time,) subscribed for me to a big circulating library. For a time I now revel’d in romance-reading of all kinds; first, the “Arabian Nights,” all the volumes, an amazing treat. Then, with sorties in very many other directions, took in Walter Scott’s novels, one after another, and his poetry, (and continue to enjoy novels and poetry to this day.)[14]

This passage will be familiar to those interested in what little Whitman had to later write about his youth in Brooklyn. Whitman’s biographers have noted the importance that Whitman has placed on his exposure to the novels and poetry he gained access to when he was subscribed by Edward Clarke to a “big circulating library.”[15] While we can’t know for sure what “big circulating library” Clarke subscribed Whitman to, it is possible that it was the circulating library run by Erastus Worthington (Sr.) and his son William Worthington, which, although under different ownership and located at various places along Fulton Street, had been in business since 1820.[16] In 1829, the library was located at 57 Fulton St., not far from the Clarke’s law office at 178 Fulton Street.[17] The Worthingtons’ circulating library most likely contained well over 1,200 volumes, which certainly would have qualified it as “big” for a circulating library in Brooklyn at that time.[18] Even more convincingly, both James B. Clarke and the Worthington family were members of St. Ann’s, Brooklyn’s Episcopal church.[19] Gay Wilson Allen has speculated that it is perhaps through Whitman’s attendance at St. Ann’s school that he got his job at Clarke’s law office.[20] In the same way it is possible to further speculate that Clarke, in subscribing Whitman to a circulating library, would have chosen the library of fellow congregants.

Whitman’s more recent biographers have not made the connection between the printers that Whitman worked for and the circulating libraries that they ran. It is not clear why this connection has been lost. In The Solitary Singer, Gay Wilson Allen made this connection explicit: “By the summer of 1832 Walt had begun working for another Brooklyn printer, Erastus Worthington, a close friend of Alden Spooner, from whom he had taken over a bookstore and circulating library. Of course, Walt made good use of the library.”[21] Although Allen makes the mistake that all of Whitman’s biographers make - confusing Erastus Worthington with his brother William (which will be clarified below) – he still draws a conceivable conclusion based on what we know of Whitman. That is, if there was a circulating library in the place where Whitman was apprenticing, he surely made good use of it.

Whitman’s Apprenticeships

Of the little information that is known about Whitman's printer's apprenticeship days in Brooklyn, a few names will be familiar to a reader of Whitman biographies: Samuel E. Clement, William Hartshorne, Alden Spooner, and Erastus Worthington. This article concerns itself especially with Spooner and, to a lesser extent, with Worthington - although not with Erastus Worthington whom Whitman’s name has usually been connected with - but rather his brother, William Worthington, as will be explained in more detail below.[22] Beyond these two individuals, I will discuss two other men who are important players in this story and new to the published biography of Whitman - Adrian Hegeman and William Bigelow.

While more biographical information will be given later in this article, a few broad points about the biographies of the four men who are central to this investigation should be highlighted up front. Alden Spooner, William Bigelow, Adrian Hegeman, and William Worthington were all proprietors of circulating libraries in Brooklyn, and all but Spooner was a proprietor of a circulating library during the same time that Whitman was working in an affiliated printing office. All except for Hegeman were printers, although Hegeman had close ties to the printing community in Brooklyn - Hegeman’s circulating library was located in the same building as Spooner’s printing office. Finally, of these four, all but William Worthington were directly involved with the organization and operation of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library[23] – Spooner, Bigelow and Hegeman all served multiple years on the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association’s board of directors.

In approaching Whitman’s connection to the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, I began by collecting what little is known about Whitman's whereabouts and activities in Brooklyn in early 1835, a time shortly before he left Brooklyn for his brief stint as a printer in Manhattan. This line of investigation led to finding out more about the Brooklyn printers Whitman apprenticed with from 1831 until 1835 – where their printing offices were located, what other activities these printers were involved in, whether these printers knew - or even worked with - each other, etc. While looking at the activities of these early Brooklyn printers, I consequently uncovered the existence of the for-profit circulating libraries that many of these printers ran in conjunction with their print shops.

The population of Brooklyn in 1830 was only a little over 15,000[24] and the business district was centered around the main commercial thoroughfare of Fulton Street. Brooklyn, during the time of Whitman’s apprenticeships, was a relatively small village, with a dense, concentrated commercial district which included the printing offices where Whitman worked. Whitman’s apprenticeship as a printer began in 1831, at the age of twelve, when he began working at the office of the Long-Island Patriot, a Democratic newspaper in Brooklyn with an office at 149 Fulton Street. The Patriot was only one of two newspapers in Brooklyn at the time, with Alden Spooner’s long-established Whig paper, the Long-Island Star, being the other. Whitman’s apprenticeship at the Patriot ended some time in the spring of 1832. It was also in 1832 that the Patriot was purchased by James A. Bennett.

It is perhaps because of this change in ownership that, in the summer of 1832, Whitman left the Patriot. Whitman biographers have stated that Whitman left the Patriot to go work for Erastus Worthington. This claim is based on Whitman’s own recollection that “I was at Worthingtons [sic] in the summer of ’32.”[25] That Whitman was at Erastus Worthington’s is impossible, however, since Erastus Worthington, Jr. died in 1827. In a footnote in The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman: The Journalism, the editors observed and corrected this long-standing error, by concluding that Whitman must have been referring to Erastus Worthington’s brother, William Worthington.[26] It is worth emphasizing this clarification here to help further elucidate Whitman’s involvement with the printing community in Brooklyn at the time.

The printing office of William Worthington was located at 95 Fulton Street in 1832. In addition to a printing office, William Worthington was also the proprietor of the circulating library which had previously been owned and run by Alden Spooner, then by his brother, Erastus Worthington, Jr. After the death of Worthington (Jr.) in 1827, his father, Erastus Worthington (Sr.) took over the business and was probably assisted by William.[27] The circulating library became solely William Worthington’s responsibility upon the death of his father in 1831.[28] If we can accept that Whitman was subscribed to the circulating library that William and Erastus Worthington (Sr.) were running in 1829, then Whitman’s apprenticeship with Worthington may not have been Whitman’s first introduction to either William Worthington or his circulating library. According to a nineteenth-century bibliography of Long Island printing, William Worthington also printed a catalogue of his circulating library some time during 1832.[29] I have not been able to locate any extant copies of this catalogue, so it is possible that the catalogue may be a bibliographic ghost. If it is not, however, and if a catalogue was printed, then it is likely that Whitman, as an apprentice in this small printing office, would have somehow assisted in the preparation of this catalogue, if not the printing of the catalogue itself.

In the summer of 1832 cholera arrived in Brooklyn and many residents fled to the countryside. Whitman later called 1832 “the bad cholera year” and recalled that he was left alone in the family’s home on Liberty Street while the rest of his family moved to the country for a few weeks during the summer.[30] It appears that William Worthington may have been among those who left Brooklyn, in this case, possibly for Richford, NY, where he was married in 1825 and where he had lived prior to his relocation in Brooklyn around 1827.[31] Before leaving Brooklyn, Worthington sold his circulating library and book store to Adrian Hegeman. With Worthington leaving town, Whitman would have been without work. Since Spooner and the Worthington family had been so close for so many years, it is reasonable to assume that this is why Whitman ended up as an apprentice at Alden Spooner’s printing office in the fall of 1832.[32]

It was some time in the fall of 1832 that Whitman began working as a compositor at the Long-Island Star, a job that would last until May 12, 1835.[33] The Long-Island Star’s proprietor and editor, Alden Spooner, provides the most direct connection between Whitman and the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library. Spooner was one of Brooklyn’s most active and civic-minded citizens. In addition to publishing the Long-Island Star for many years, Spooner was also instrumental in procuring the village charter for Brooklyn in 1816, and he later promoted its incorporation as a city in 1834. Spooner also helped establish Fort Greene Park, the Brooklyn Gas Light Company, the Female Seminary in Brooklyn, and the Lyceum of Natural History.[34] He was also one of the founders of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association in 1823 and served on its board of directors in 1824, then again from 1826 to 1831, and finally from 1833 until 1835.

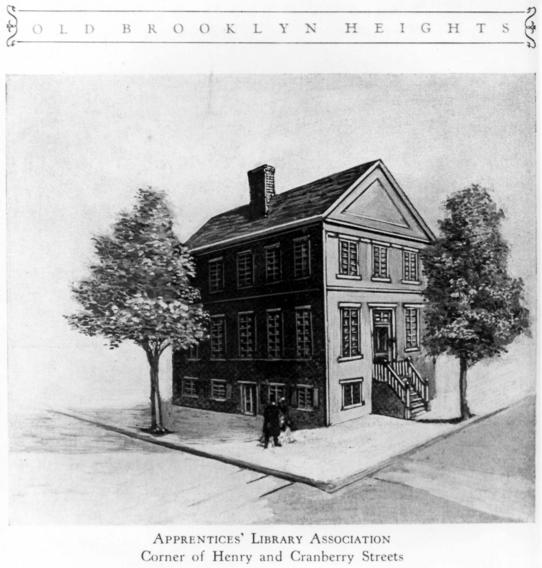

The Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library was originally housed in a small building at 143 Fulton Street, where it was located from its founding in 1823 until May 1826 when a building erected for the purpose of housing the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library was completed. That building stood at the southwest corner Cranberry and Henry Streets, about five blocks from the office of the Long-Island Star at 57 Fulton Street. But Spooner was not the only person directly involved with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library during the period that Whitman was working at the office of the Long-Island Star.

Some time between May of 1832 and May of 1833, Adrian Hegeman had purchased the bookstore and circulating library of William Worthington and relocated both the bookstore and the circulating library from Worthington’s location at 95 Fulton Street back to its previous location at 57 Fulton Street, in the same building that housed the office of the Long-Island Star. In addition to running the bookstore and circulating library, Adrian Hegeman was also the post master for Brooklyn, during a time when the postal duties for the town were carried out by one person and when the post office was usually located in the same building that housed the other business that the postmaster was engaged in. During the entire time that Whitman was an apprentice for Spooner, the Brooklyn post office and Hegeman’s circulating library, stationery and book store were all located in the same building as the printing office of the Long-Island Star. Additionally, directly next door at 55 Fulton Street, William Bigelow began running his own circulating library starting in 1834, in addition to his previously established bookstore, stationery store, and printing office.[35] By the time Whitman started working at Spooner’s printing office at 57 Fulton Street in the fall of 1832, Bigelow had been established next door for at least a year. By 1833, Spooner and Bigelow had known each other for at least twenty years and by the mid-1830s they were also publishing jointly – the 1834/35 Brooklyn directory was co-published by Alden Spooner and William Bigelow.

Considering that Whitman, later in his life, called his subscription to a circulating library “the signal event of my life up to that time,” we may comfortably assume that Whitman gained a certain familiarity with the circulating libraries of Adrian Hegeman and William Bigelow, since Hegeman’s circulating library was located in the same building that Whitman was working in and Bigelow’s circulating library was located directly next door. Whitman’s presence as an apprentice in Alden Spooner’s printing office, as well as the interest he presumably showed in these circulating libraries, may well have resulted in his being asked to help with some of the duties involved in running a circulating library, no matter how menial. Even if this is not the case, one set of conclusions may be clearly drawn: Whitman knew Alden Spooner, William Bigelow and Adrian Hegeman, and worked with them, during his apprenticeship at the Long-Island Star at 57 Fulton Street from the fall of 1832 until May of 1835, at the same time that two circulating libraries were in business at 55 and 57 Fulton Street.

A circulating library of 1830s Brooklyn does not really have a correlative to any of today’s libraries. The shelves of the library were not open and browsable, but subscribers were given a printed catalogue to select what they wanted from the library. The catalogues themselves were often arranged alphabetically by title within loosely drawn genre categories such as “Novels, Tales, and Romances” or “History, Biography, Voyages, Travels.”[36] Librarianship was not professionalized, as it is today, and the role of the librarian was more akin to that of the modern circulation desk clerk and book-shelver. The librarian’s duties at a circulating library mostly consisted of keeping track of who had borrowed which books, reshelving returned books, retrieving books that had been requested, as well as keeping track of subscriptions to the library. Given Whitman’s enthusiasm for the earlier circulating library that he had been subscribed to by Edward Clarke, it is easy to imagine that he tried to involve himself with the circulating libraries of Hegeman and Bigelow. While it is only speculation, it is easy to imagine that Spooner, Hegeman, and Bigelow observed Whitman’s enthusiasm and interest (and possibly even his ability) and, because of a particular – and, frankly, desperate – situation at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, asked Whitman to perform certain duties as “acting librarian.”

Demise of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library and Whitman’s Appointment in 1835

The Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association was founded in 1823 by a group of citizens interested in forming a library whose main purpose was to gratuitously provide books to the apprentices of the village. The Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library was a free library – Brooklyn’s first free library – and was open for the gratuitous use of all of the apprentices in the village of Brooklyn, but also allowed for any member of the village to pay yearly dues to both support the institution as well as gain access to its collections.[37] The Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library was a not-for-profit library with a stated mission of “extending the benefits of knowledge to that portion of our Youth who are engaged in learning the Mechanic Arts, and thereby qualify them for becoming useful and respectable members of society.”[38]

Alden Spooner and William Bigelow shared an interest and involvement in establishing libraries in Brooklyn as early as 1813 with their attempt to establish the Kings County Union Library.[39] While that venture does not appear to have been successful, both men were involved in the successful establishment of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association ten years later. Both Alden Spooner and William Bigelow were among those who attended the first meeting of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library at William Stephenson’s tavern, 160 Fulton Street, on August 7, 1823.[40] Alden Spooner, William Bigelow, and Adrian Hegeman also each served many years on the board of directors of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association (see table below).

Table A. Tenures of Directors of Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association Relevant to This Investigation

Name Title Years Serving That Position

Alden Spooner Director 1824, 1826-31, 1833-35

William Bigelow Director 1826-31,1833-35

Adrian Hegeman Director 1826, 1830-31

As can be seen in the table above, both Spooner and Bigelow were on the board of directors for almost the entire time that Whitman was working in Spooner’s office as an apprentice (i.e. fall 1832 – May 1835). And while Adrian Hegeman did not serve on the board of directors at the Apprentices’ Library concurrent with Whitman’s apprenticeship with Spooner, he was a close business associate of both men. He was also working in Spooner’s office during this period, and had served with both men on the board of directors during his earlier involvement with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library.

The history of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library and its association with Brooklyn’s early printers is a history to be told elsewhere, but for the purposes of this investigation, the organization’s eventual demise in 1835 is of most interest. Only three substantial histories of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library have been written – Henry Stiles included a history of the Apprentices’ Library in his three-volume A History of the city of Brooklyn : Including the Old Town and Village of Brooklyn, the Town of Bushwick, and the Village and City of Williamsburgh; Duncan Littlejohn’s unpublished manuscript Records of the Brooklyn Institute, 1823 to 1873 : With Occasional Explanatory Remarks, List of Directors and Officers, and Some Reminiscences of Prominent Individuals in Connection Therewith, and Ralph Foster Weld’s chapter on the Apprentices’ Library in Brooklyn Village: 1816-1834.[41] All three histories draw heavily on the minutes of the meetings of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association and contemporary newspapers as their sources. Because the Brooklyn Museum, especially its library, traces its history back to the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library,[42] histories of the Brooklyn Museum library contain brief histories of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library as well.[43]

Because the primary sources that remain from the Apprentices’ Library are limited – consisting mostly of the minutes books from annual meetings of the association, some broadsides, a printed catalogue of the collection, as well as articles and notices in early nineteenth-century Brooklyn newspapers[44] – the facts used to tell the story of the library are generally repeated in each of the histories. Some of the histories include more of the facts than others, sometimes stressing the organization’s successes over its failures. Interpretations of these facts, and attempts at viewing the Apprentices’ Library as a part of the community of the village of Brooklyn vary greatly. The eventual failure of the enterprise, which closed in 1835, is especially illustrative of this and, as it concerns Whitman’s involvement with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, is worth examining in closer detail.

Henry Stiles’ account of the Apprentices’ Library is, for the most part, a fairly buoyant account of a library that was founded by a group of men noted for their richness in character and moral strength who altruistically form a library for the benefit of the youth of the village.[45] After twelve years, the Apprentices’ Library, by Stiles’ account, disappears almost as mythically as it appears. Here is Stiles’ complete account of the last few years of the library’s existence:

But, in 1833, Robert Snow [president of the library from its founding until 1831], its life long friend, died. Five years before, Robert Nichols [Secretary 1824-1828] had removed from Brooklyn; others of its originators had left the place, and the pursuits of many of those who remained withdrew them from its immediate neighborhood. The readers gradually fell off, the records show conclusively that the institution was becoming deeply embarrassed by debt; and finally, in 1836, the building was sold to the city for $11,000, and the books were boxed and stored away for preservation. But the work, so generously planned and so happily begun, was not destined to be an ignoble failure.[46]

Stiles continues from there and discusses the reorganization of the Apprentices’ Library in 1840, which would eventually result in the official founding of the Brooklyn Institute in 1843. While Stiles’ history is clearly a product of the time during which he wrote it, it can still be seen in the passage above that Stiles feels that it is his duty to discuss some of the negative aspects of the organization, although he does not dwell on them for long or in any detail.

Duncan Littlejohn’s account of the Apprentices’ Library is essentially an editorial distillation of the minutes books of the Apprentices’ Library and the Brooklyn Institute. Littlejohn was treasurer of the Brooklyn Institute when he wrote his history of the organization. Because of his involvement with the Brooklyn Institute, one might expect a history that focuses on the successes of the organization and judiciously ignores its failures. Instead, Littlejohn’s account shows that starting in 1828, the Apprentices’ Library began to encounter great difficulties. Of the reading room which was opened in 1826, Littlejohn records that in November 1827, “the free reading room so auspiciously commenced had recently met with so little sympathy and support, the directors reluctantly had to abandon the enterprise after an unsatisfactory experience of a year.”[47] This is much more revealing than Stiles’ history which gives an optimistic account of the opening of the reading room, but does not mention its closure at all.[48] In all, Littlejohn’s choice of what to extract and present from the minutes provides a clear picture of an organization in decline over a number of years, with concerns about a declining readership and financial problems, all accounted in detail.[49]

Weld, writing nearly fifty years later, places his account of the Apprentices’ Library in the context of community life in the village of Brooklyn.[50] Weld’s account of the Apprentices’ Library is of an organization doomed from the start by “an elaborate if vague program”[51] and by observing that, unlike the more successful apprentices’ library established in New York in 1820 by the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library did not have an already established mechanics organization which could serve both as a sponsoring body of the Apprentices’ Library and provide managers from within its own ranks. Instead, Weld writes “control and management remained in the hands of a group of pious patrons, who regarded the moral oversight of the community as their especial charge.”[52] Weld’s narration of the demise of the library follows Littlejohn’s in its unflinching look at an organization which was in decline for a number of years and recorded this decline in its meeting minutes. Yet this decline was public in nature too, and Weld points to many of the appeals made in the both the Long-Island Star and Long Island Patriot, which chastise masters for not encouraging their apprentices to use the library as well as repeated appeals for nominal members of the library to pay their initiation fees.[53] Both Spooner and Bigelow were especially active in trying to keep the organization viable, beyond Spooner’s publication of advertisements in the Long-Island Star. To cite but one example, in 1833 (while Whitman was working for Spooner), both Spooner and Bigelow, along with Gabriel Furman, were appointed to head a committee in charge of canvassing the village of Brooklyn for cash donations for the library, after earlier attempts at placing advertisements in Spooner’s paper failed to elicit donations from the citizens of Brooklyn.[54]

A timeline of the Brooklyn Museum published in 1967, which goes far back enough to include its earlier incarnations, the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library and the Brooklyn Institute, states the following for 1835: “Walt Whitman becomes the temporary librarian. Library closes because of lack of interest.”[55] This frank assessment, while perhaps unintentionally comical, serves to helpfully highlight a provocative question: why was Whitman appointed acting librarian at a point when the library appeared to be on the verge of folding? A look at the minutes from two meetings at the end of January 1835 reveals an organization in dire straits.

The minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association held on January 30, 1835, reads as follows:

Resolved that the situation of the financial concerns of this Institution is such, as to render it absolutely necessary in this Board in the discharge of their duty towards the Stockholders of this Association to reduce as much as possible their expenses, and therefore

Resolved, that this Board do abolish the office of Porter and Librarian from and after the first day of February next and that the Secretary do acquaint Mr. Debevoise the present Porter and Librarian with the making of this Resolve –

Resolved that this Board do adjourn until tomorrow evening at 7 o’clock for the purpose of taking into consideration the propriety of disposing of the Library so connected with this Institution to the Mechanics Society of this City.[56]

As can be seen above, the office of Porter and Librarian, a paid position, was abolished on January 30, 1835. This decision, while severe, doesn’t seem especially surprising considering the financial trouble that the organization appeared to be in at the time, evidenced by the board’s consideration of how to “reduce as much as possible their expenses” and whether this should include the disposal of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library to the Mechanics & Manufacturers Society of Kings County. (Perhaps not coincidentally, two of the board members of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library – Spooner and Bigelow – were also on the governing board of the Mechanics Society, an organization that had been formed in Brooklyn three years earlier.[57])

The minutes from the meeting held at seven o’clock the very next evening, January 31, 1835, read (in their entirety):

The Board met pursuant to adjournment. Present the President and all the members – The Secretary reported that he had acquainted Mr. Debevoise the present Porter and Librarian with the Resolution of the last meeting abolishing the office of Porter and Librarian on and after February 1st next –

Walter Whitman acting Librarian presented a report this evening, in which it is stated that there are now about 1200 volumes in the Library in a proper state for being drawn out; and that the number of Readers is 172 – which Report was accepted and ordered to be filed.

The special object for which this meeting was held, the disposing of the Library to the Mechanics Society of this City, was then called up for consideration; and after much discussion it was deemed advisable not so to dispose of the said Library [so?] at present. Adjourned.[58]

While the minutes do not reveal the specifics of any discussion held at the meeting, it is evident that Mr. Debevoise was informed that his position as Porter/Librarian had been eliminated, but also that Walter Whitman, in his role as acting librarian, filed a report on the current status of the libraries collections and readers. It would appear from the minutes, that the very day after the (paid) position of Librarian and Porter was eliminated, a fifteen-year old printer’s apprentice was asked to take over the duties. The minutes for the January 31st meeting also make explicit the reason for the meeting – the consideration as to whether the Apprentices’ Library should be disposed to the Mechanics’ Society, an action which was decided against. It is in this context that we must view the paragraph stating Whitman’s report on the number of readers and the number of volumes in the library. It appears that the reason Whitman was asked to report on the state of the library was to give the library directors a better sense of the state of the library so that they could consider whether or not it should – or could – be sold. Although we can’t know for sure, Whitman probably performed these duties without pay, considering the financial situation of the institution, his position as a fifteen-year old apprentice, and that the paid position of Librarian/Porter had been abolished the day before. In effect, it would seem that two of the influential directors of the institution, Alden Spooner and William Bigelow, might have volunteered the services of a fifteen-year-old apprentice who they knew had previous experience with libraries through his exposure to the circulating libraries of William Worthington, William Bigelow, and Adrian Hegeman, during the previous three years.

It is not clear how long Whitman served in his role of acting librarian. The minutes from the January 31, 1835 are the last minutes kept of any meetings before the institution eventually closed and sold off its building in 1836. Whitman’s apprenticeship with Spooner ended on May 12, 1835, and he left for Manhattan soon after,[59] so the longest period he may have served in his capacity as librarian is a little over three months. It is also possible that after having counted the books and readers and reported those numbers at the January 31st meeting, that his duties may have ended there. While the length of his tenure is uncertain, what is certain is that Walt Whitman, because of the circumstances of his apprenticeship and, most likely, because of both his experience and interest in circulating libraries, was appointed “acting librarian” of a very different type of library - the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library - at the end of January 1835.

Why Whitman Never Wrote About It

If libraries were so important to Whitman, why didn’t he write about his experience as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library? It is clear that the Apprentices’ Library made an impression on him, since he wrote about it later in life. In Brooklyniana No. 15, originally published in the Brooklyn Standard in the early 1860s, Whitman writes about the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, focusing almost exclusively on his account of being taken up in the arms of the Marquis de Lafayette at the laying of the cornerstone of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library building in 1825, one of three different versions of that event that Whitman wrote.[60] What is conspicuously absent among Whitman’s written reminiscences about the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, however, is any mention of his role as acting librarian in 1835. Present almost from the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library’s inception, Whitman appears to have been present to witness the unfortunate demise of the organization as well, but did not write about it.

After looking at both Specimen Days and the Brooklyniana pieces, it becomes clear why Whitman didn’t choose to write about his experience as acting librarian. Whitman’s writings about the Brooklyn of his youth all tend to have an air of nostalgia surrounding them. In Brooklyniana No. 17, Whitman writes about the prominent citizens who lived in Brooklyn in the 1830s, stating “Hardly a place in the United States, not even the oldest and most ‘moral’ settlements of New England, can boast a better list of these citizens of integrity and general worth,”[61] before naming a number of prominent citizens of Brooklyn from the 1830s – a long list that includes Alden Spooner, Adrian Hegeman, and the names of seven other men who, among many other activities, served on the governing board of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library. Given Whitman’s approach to autobiography, it is no surprise that he didn’t deem his brief stint as acting librarian at the Apprentices’ Library as worthy of recording, especially considering that he assumed this role at a time when the Apprentices’ Library was not, by all accounts, a thriving organization. From Whitman’s point of view, there was probably not much of a story in being asked by the printers that he apprenticed with (and who happened to be in charge of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library) to do the free work of “acting librarian” for an organization that was clearly nearing the end of its existence.

It is worth speculating about what Whitman’s role might have been if the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library had chosen a different route in their attempts to become solvent. What might Whitman’s influence have been if Spooner, Bigelow, and the other directors of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library had followed the path of the Boston Mechanics Apprentices’ Library which, faced with a similar situation as the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, confronted its own crisis of existence starting in 1828? Instead of relying on a board of directors to continue to run the apprentices’ library, as happened with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library, the Boston Mechanics Apprentices’ Library turned to the apprentices to help save the organization, by giving them the right to operate the library themselves. Among the rights the apprentices gained was the authority to decide what books should be purchased for the library. This change “made the organization a lively one, and the book collection soon ran to Scott novels and adventure stories.”[62] That is, when those who used the library (i.e. the apprentices) were able to decide what books they wanted in their library, they chose the type of books that the founders of apprentices’ libraries were trying to keep out of their hands (i.e. novels, adventure stories, etc.), which were also exactly the type of books that made circulating libraries so successful. Sir Walter Scott’s novels, mentioned in the previous quote, were, of course, enormously popular in the United States during the first few decades of the nineteenth century and, more often than not, the copies that were read were copies borrowed, for a fee, from a circulating library.

If the apprentices of Brooklyn had gained control of their apprentices’ library there is reason to believe that the results would have been similar. Whitman would certainly have made a case for getting Scott’s novels on the shelves of the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library. In addition to mentioning Scott in the same breath as circulating libraries in Specimen Days, Whitman also made it clear how much he felt Scott influenced his own poetry: “If you could reduce the Leaves [of Grass] to their elements you would see Scott unmistakably active at the roots.”[63] And so we might also say that if you could reduce the elements of Whitman’s service at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library to its elements, you would see some of Brooklyn’s printers and circulating libraries active at the roots.

Conclusion

It is my hope that this current investigation into Whitman’s connection to the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library through his exposure to circulating libraries is just a beginning. Whitman’s early exposure to circulating libraries has been noted and highlighted by others in the past, but with little effort to deduce what libraries Whitman may have had access to. The details of Whitman's exposure to specific Brooklyn circulating libraries as well as Whitman’s ties to the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library should provide other researchers opportunities to gain more insight into Whitman's early life in Brooklyn, including his early self-education.

Additionally, Whitman’s involvement with the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library Association pre-dates his later, and much more documented interest in the Apprentices’ Library’s reorganized successor, the Brooklyn Institute. While the Apprentices’ Library struggled to gain a significant foothold in the cultural life on Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Institute was an undeniable success. In 1847, during his time as editor at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Whitman wrote about an upcoming exhibition of paintings at the Brooklyn Institute, in which he made his opinion about the Institute’s importance quite plain: “This truly valuable institution is now about to commence its usual career of usefulness during the winter months. Being decidedly the most interesting feature of Brooklyn life, it has so insinuated itself in the affections of a large class of our citizens that its absence would create a blank much to be deplored.”[64] But that was in 1847, over a decade after the less successful Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library closed its doors.

Endnotes

[1]. In addition to periodical literature published about Whitman’s life, I would mention specifically the major Whitman biographies, all of which discuss the years addressed in this article: Gay Wilson Allen, The Solitary Singer, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967); Justin Kaplan, Walt Whitman: A Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980); David S. Reynolds, Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography (New York: Vintage Books, 1995); Gary Schmidgall, Walt Whitman: A Gay Life (New York: Dutton, 1997); ); Jerome Loving, Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1999)

[2]. These publications include The Brooklyn Museum Handbook (Brooklyn, NY: The Brooklyn Museum, 1967); Deirdre Lawrence, “A History of the Brooklyn Museum Libraries,” The Bookmark (Winter 1985): 92-93; Deirdre Lawrence, “From Library to Art Museum: The Evolution of the Brooklyn Museum,” The International Journal of Museum Management and Curatorship 6 (1987): 381-386; Deirdre Lawrence, “The Evolution of a Library: The Brooklyn Museum of Art Libraries and Archives,” Art Documentation 18.1 (1999): 10-13; Deirdre Lawrence, “Walt Whitman and the Arts in Brooklyn In Celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Publication of Leaves of Grass” http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/features/2005/whitman/ (29 September 2006). For the most recent instance, see Teresa Carbone “‘Ardent, Radical, and Progressive’: Augustus Graham, Walt Whitman, and American Art at The Brooklyn Institute.” American Paintings in the Brooklyn Museum : Artists Born by 1876. (Brooklyn, N.Y. : Brooklyn Museum, 2006), 1:13-25. Whitman’s role as acting librarian at the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library is mentioned in volume 1, p. 17.

[3]. Jeffrey Croteau, “Yet More American Circulating Libraries: A Preliminary Checklist of Brooklyn (N.Y.) Circulating Libraries.” Library History 22.3 (November 2006).

[4]. W.J. Rorabaugh, The Craft Apprentice: From Franklin to the Machine Age in America. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 121-124.

[5]. See Tom Glynn, “Books for a Reformed Republic: The Apprentices’ Library of New York City, 1820-1865.” Libraries & Culture 34.4 (1999): 347-72. The reach of Wood’s influence on establishing apprentices’ libraries is mentioned on p. 352.

[6]. Haynes McMullen, American Libraries Before 1876. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000), 70-71.

[7]. For an excellent overview of the history of circulating libraries in the United States, see David Kaser, A Book for a Sixpence: The Circulating Library in America (Pittsburgh: Beta Phi Mu, 1980).

[8]. Ralph Foster Weld, Brooklyn Village: 1816-1834. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1938), 133-34. Kaser also discusses this at length.

[9]. For the lasting influence of Whitman’s printing apprenticeship, see Reynolds, 46-47 and Loving, 34-35. For Whitman’s introduction to literature through circulating libraries, see Allen, 17, and Reynolds, 40.

[10]. Among the many claims, most point to Whitman’s love for Sir Walter Scott’s work, which began with his introduction to circulating libraries, and with his involvement in setting type for ten pages of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass.

[11]. See Robert J. Swan, “The Brooklyn Directories: Stochastic History,” The Journal of Long Island History 11.2 (1975): 39-55.

[12]. Schmidgall writes “from boyhood called Walt by his family and friends, was known to the world, mainly through his journalistic editing and writing, as ‘Walter’ or ‘W.’ Whitman” (3). The poetic persona of “Walt Whitman” was, of course, far from being realized in 1835.

[13]. By 1871, there was at least one other Walt Whitman in the area, as a short entry in the March 29, 1871 issue of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reveals: “The poet Walt Whitman was not the Walter Whitman killed on the Hudson River Railroad. If the telegrapher who sent the item had not been a dolt, he would have stated as much at first, and saved Walt’s Brooklyn friends a good deal of anxiety.” (4)

[14]. Walt Whitman, Prose Works 1892, ed. Floyd Stovall (New York: New York University Press, 1963), 1:13.

[15]. Loving, 32-33. Loving remarks that Whitman placed enormous importance on this, also highlighting Whitman’s phrase, the “the signal event of my life up to that time.” See also Reynolds, 44 and Allen, 17.

[16]. The history of this particular circulating library – known for much of its existence simply as the Brooklyn Circulating Library – is a long and complicated one. For the purposes of this article, it is important to note that it appears that Erastus Worthington (Sr.) and his son, William Worthington, may have been running the circulating library jointly in 1829. They fell heir to the circulating library and bookstore previously run by Erastus Worthington (Jr.), who was a printer, and Alden Spooner’s business partner for many years, and who died at the age of 38 of consumption in 1827. An advertisement for the circulating library in the 1829 Brooklyn directory only refers to “E. Worthington, Circulating Library,” but in the alphabetical directory itself, his son, William, is listed as the proprietor of the bookstore at the same location. Given that the bookstore and circulating library were related businesses, it is likely that both men may have shared the responsibilities of running the businesses. Erastus Worthington, Sr. died in 1831; the 1832/1833 Brooklyn directory contains an advertisement for “Wm. Worthington’s Circulating Library.”

[17]. Spooner’s Brooklyn Directory, for the Year 1829, (Brooklyn, NY: Alden Spooner, 1829). All addresses are taken from the Brooklyn directory for the corresponding year. Alden Spooner published the Brooklyn directory from 1822 until 1835, except for 1827 and 1828 (when no directory was published) and 1833/34 (when the directory was published by Nicholas & Delaree).

[18]. According to an advertisement in the October 13, 1825 issue of the Long-Island Star, Spooner’s circulating library consisted of 1,200 volumes. Spooner sold his circulating library and bookstore to his partner, Erastus Worthington, Jr. in 1827 (see footnote 16). As to whether any other circulating libraries were in business during the period mentioned by Whitman in Specimen Days, I was able to find no evidence of any other circulating libraries in Brooklyn except for Erastus and William Worthington’s during 1829 and 1830, although others may certainly have existed.

[19]. Weld, 66.

[20]. Allen, 17.

[21]. Allen, 21.

[22]. Although I am mostly concerned with William Worthington in this article, it is worth trying to clear up some of the confusion between his brother, Erastus Worthington, Jr. (1789-1827), and his father, Erastus Worthington, Sr. (1761-1831). In print at least, both men appear to have gone simply by the name “Erastus Worthington” which has caused Brooklyn historians such as Henry Stiles and Ralph Weld to confuse the two. Worthington (Jr.) was a printer and worked as Alden Spooner’s business partner for many years. Worthington’s father, Erastus Worthington (Sr.), was the postmaster in Brooklyn from 1826 until 1831 and does not appear to have been a printer. Upon his son’s death, Worthington (Sr.) took over the circulating library and bookshop, using the name “E. Worthington” an effort which very well may have left customers at ease and historians confused.

[23]. However, Worthington’s brother, Erastus Worthington, Jr., was an important Brooklyn printer, arguably more important than William. Erastus Worthington, Jr. also served as the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library’s first librarian, from 1824 until 1827.

[24]. Margaret Latimer, ed. Brooklyn Almanac: Illustrations, Facts, Figures, People, Buildings, Books (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Educational & Cultural Alliance, 1984), 21.

[25]. Emory Holloway, The Uncollected Poetry and Prose of Walt Whitman, (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1972), 2:86. It may be Holloway who first suggested that the Worthington that Whitman referred to was Erastus Worthington: “I have been unable to discover than any city directories were published in the years 1827-1835 [sic]; but Spooner’s directory for 1826 gives “Worthington, Erastus, jun., printer” (2:296).

[26]. Walt Whitman. The Collected Writings of Walt Whitman: The Journalism (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 1998), 1:xliv. The correction may be found in footnote 9.

[27]. See footnote 16 above.

[28]. The library is referred to as “Wm. Worthington’s Circulating Library” in an advertisement placed in the 1832/33 Brooklyn directory.

[29]. Henry Onderdonk, Jr. “Bibliography of Long Island.” Antiquities of Long Island. Gabriel Furman. (New York: J.W. Bouton, 1874), 435-69. An entry on p. 469 reads “Worthington, Wm. Catalogue of his Cir. Lib., Br. 1832. 12mo, pp. 20.”

[30]. For Whitman’s experience recollections of the cholera summer of 1832, see Kaplan, 72-73. There were ninety cases of cholera in Brooklyn between June 20 and July 25, 1832, of which thirty-five died; see Henry R. Stiles, A History of the City of Brooklyn : Including the Old Town and Village of Brooklyn, the Town of Bushwick, and the Village and City of Williamsburgh [Originally published in 1870] (Bowie, Md. : Heritage Books, 1993), 2:237. For an excellent overview of the impact of cholera in New York, just across the East River from Brooklyn, see Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 13-98.

[31]. William Worthington was still in Brooklyn as late as May 1832, as evidenced by an advertisement for his circulating library appeared in the 1832/33 Brooklyn directory. However, by May, 1833, Adrian Hegeman was able to announce in an advertisement in the 1833/34 Brooklyn directory that he had purchased “the Circulating Library and Book Store, formerly in possession of Mr. William Worthington.” Also, see George Worthington, The Genealogy of the Worthington Family (N.p., 1894), 205, 298. “William Worthington of Richford N.Y. married, Oct. 4, 1825, Eliza Caldwell Phelps of same place…They removed to Brooklyn, N.Y. about 1827, returning to Richford about 1837.” It is possible that George Worthington has the date wrong (his death date for Erastus Worthington (Sr.) is “about 1836” (205) and is therefore off by five years), or that Worthington left Brooklyn and relocated somewhere else first before arriving in Richford.

[32]. Esther Littleford Woodworth-Barnes, Spooner Saga: Judah Paddock Spooner and His Wife Deborah Douglas of Connecticut and Vermont and Their Descendants (Boston, MA: Newbury Street Press, 1997), 26. William Worthington served as a witness to Alden Spooner’s second marriage to Mary Ann Wetmore on March 23, 1831. Erastus Worthington, Jr. was highly regarded by Spooner as well: “He proved a most excellent man, and continued to be connected with me to the day of his death. I loved him as a brother, and always treated him as a confidential friend.” Alden Spooner, “A Brief Sketch of the Life of Alden Spooner, Written by Himself for the Instruction and Information of His Children and Their Descendants,” Spooner Saga, 223-249. Spooner’s praise for Erastus Worthington is on p. 248.

[33]. Joann P. Krieg, A Whitman Chronology (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1998), 7.

[34]. Brooklyn Before the Bridge: American Paintings from the Long Island Historical Society. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1982), 68. For an overview of Spooner’s life, I would refer the reader to Marie Ruth Wall, “Alden Spooner: Printer and Patriot,” Journal of Long Island History 10.2 (1974): 33-46.

[35]. An advertisement for Bigelow’s circulating library may be found in the Brooklyn Directory for 1834-35 (Brooklyn: Spooner & Bigelow, 1834). Ten years before, in 1823 and 1824, Bigelow was listed in the Brooklyn directory as a bookbinder at 50 Fulton St., the same address as Spooner’s Long-Island Star at that time. After a few years of working at 67 ½ Fulton Street, Bigelow relocated to 55 Fulton Street in 1830 or 1831, in the building directly next door to where Spooner’s and Hegeman’s businesses were located.

[36]. These examples are from the Catalogue of books in the Brooklyn Circulating Library: kept at the offices of the Long-Island Star, Fulton-Street, Brooklyn (Brooklyn: Printed by E. Worthington, 1821) and are typical of catalogues that Whitman might have seen – or even helped print.

[37]. Apprentices’ Library Association. Constitution of the Apprentices’ Library Association of the Village of Brooklyn. (Brooklyn: G.L. Birch, 1823), 4.

[38]. Apprentices’ Library Association Constitution, 3.

[39]. William Bigelow, who became the proprietor of his own circulating library in the 1830s, announced in the February 10, 1813 edition of the Long-Island Star that there would be a meeting at his house to discuss the possibilities of forming the Kings County Union Library, “for the promotion of religion, virtue, and morality, and the diffusion of general and useful knowledge.” A month later, a small notice on the front page of the March 10, 1813 Long-Island Star, published at that time by Alden Spooner and his apprentice Henry C. Sleight, announced that subscribers could sign up at the offices of the Star should they be interested. It doesn’t appear that this library ever got beyond the planning stages and no sources consulted mention this proposed library although Spooner and Bigelow’s involvement illustrates, in a way that has not yet been shown, that both individuals were involved in Brooklyn libraries as early as 1813.

[40]. Stiles, 3: 886-888.

[41]. Henry R. Stiles, "The Apprentices' Library Association of the Village of Brooklyn" 3: 886-896. A History of the City of Brooklyn : Including the Old Town and Village of Brooklyn, the Town of Bushwick, and the Village and City of Williamsburgh. [Originally published in 1870] Bowie, Md. : Heritage Books, 1993; Duncan Littlejohn, Records of the Brooklyn Institute, 1823 to 1873 : With Occasional Explanatory Remarks, List of Directors and Officers, and Some Reminiscences of Prominent Individuals in Connection Therewith. Ts 1879. Brooklyn Museum Libraries & Archives; Ralph Foster Weld, Brooklyn Village: 1816-1834. New York: Columbia University Press, 1938.

[42]. After dissolving in 1835, the Apprentices’ Library reorganized in 1840 and, in 1843, was officially reorganized as The Brooklyn Institute. This organization eventually grew into The Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, the parent organization of the Brooklyn Museum.

[43]. See articles by Deirdre Lawrence in footnote 2.

[44]. In addition to the Brooklyn Museum Libraries & Archives, original material from the Brooklyn Apprentices’ Library is in the collections of the Brooklyn Historical Society and the New-York Historical Society.

[45]. Stiles, 3: 888.

[46]. Stiles, 3: 892.

[47]. Littlejohn, 7.

[48]. See Stiles, 3: 891: “In 1826, a reading room was opened, and furnished, through the kindness of Mr. Spooner, of the Star, and Mr. Silliman, editor of the New York Times, with most of the best papers published in the United States and with several of the leading American and foreign periodicals, and was made free to the use of all, whether citizens or strangers, every day in the week, except the sabbath.”

[49]. See especially Littlejohn, 7-10.

[50]. Brooklyn was incorporated as a village in 1816, and then again as a city in 1834. Brooklyn was eventually consolidated with New York City in 1898.

[51]. Weld, 196.

[52]. Weld, 196.

[53]. Weld, 198-199.

[54]. Weld, 330 (note 7).

[55]. Brooklyn Museum. The Brooklyn Museum Handbook. (Brooklyn, NY: The Brooklyn Museum, 1967), 518.

[56]. This is the bulk of the entry for January 30, 1835; it is preceded by a list of attending members of the board and with recognition that an election had just taken place and that the attending officers were elected. Minutes of the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library Association, 1:84. Brooklyn Museum Archives.

[57]. The 1834/35 Brooklyn Directory, 100. The list of the leaders of the Mechanics Society includes Spooner as Corresponding Secretary and Bigelow as Collector. According to the 1835/36 Brooklyn Directory, both Spooner and Bigelow continued to hold those positions.

[58]. Minutes of the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library Association, 1:84. Brooklyn Museum Archives.

[59]. See Krieg, 7.

[60]. Walt Whitman, Walt Whitman’s New York: From Manhattan to Montauk, ed. Henry M. Christman (New York: Macmillan Company, 1963), 119-127.

[61]. Whitman’s New York, 140-142.

[62]. Rorabaugh, 122.

[63]. See Reynolds, 40-41, for a concise treatment of Whitman’s admission of Scott’s influence on his work, especially Leaves of Grass.

[64]. Walt Whitman, "Brooklyn Institute—Exhibition of Paintings—Lectures—Concerts," Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 6, 1847.