Whitman on Broadway – The Poet of the Present Contemplates the Past

By Roberta Munoz

Bustling Broadway c. 1850’s (Unknown Artist via Getty Images)

When Walt Whitman writes about the “great thoroughfare” of Broadway in Manhattan the energy almost breaks the page. It was, and still is, a place where … million-footed Manhattan unpent descends to her pavements…entirely given up to foot-passengers and foot-standers, when the mass is densest [1].

Whitman saw Broadway as a rushing land river, pouring down through the center of Manhattan [2]. His descriptions of Broadway overflow the page in their diversity and profusion - bronze, brahmin, and llama, Mandarin, farmer, merchant, mechanic, and fisherman, The singing-girl and the dancing-girl, the ecstatic persons, the secluded emperors…[3]

A river evokes the idea of power, abundance, renewal and also, crucially, timelessness and an eternal now – ever changing and ever the same. There is some dissonance then when Whitman deliberately steps away from the endless sliding, mincing, shuffling feet [4] of the vivid present to observe the distant past.

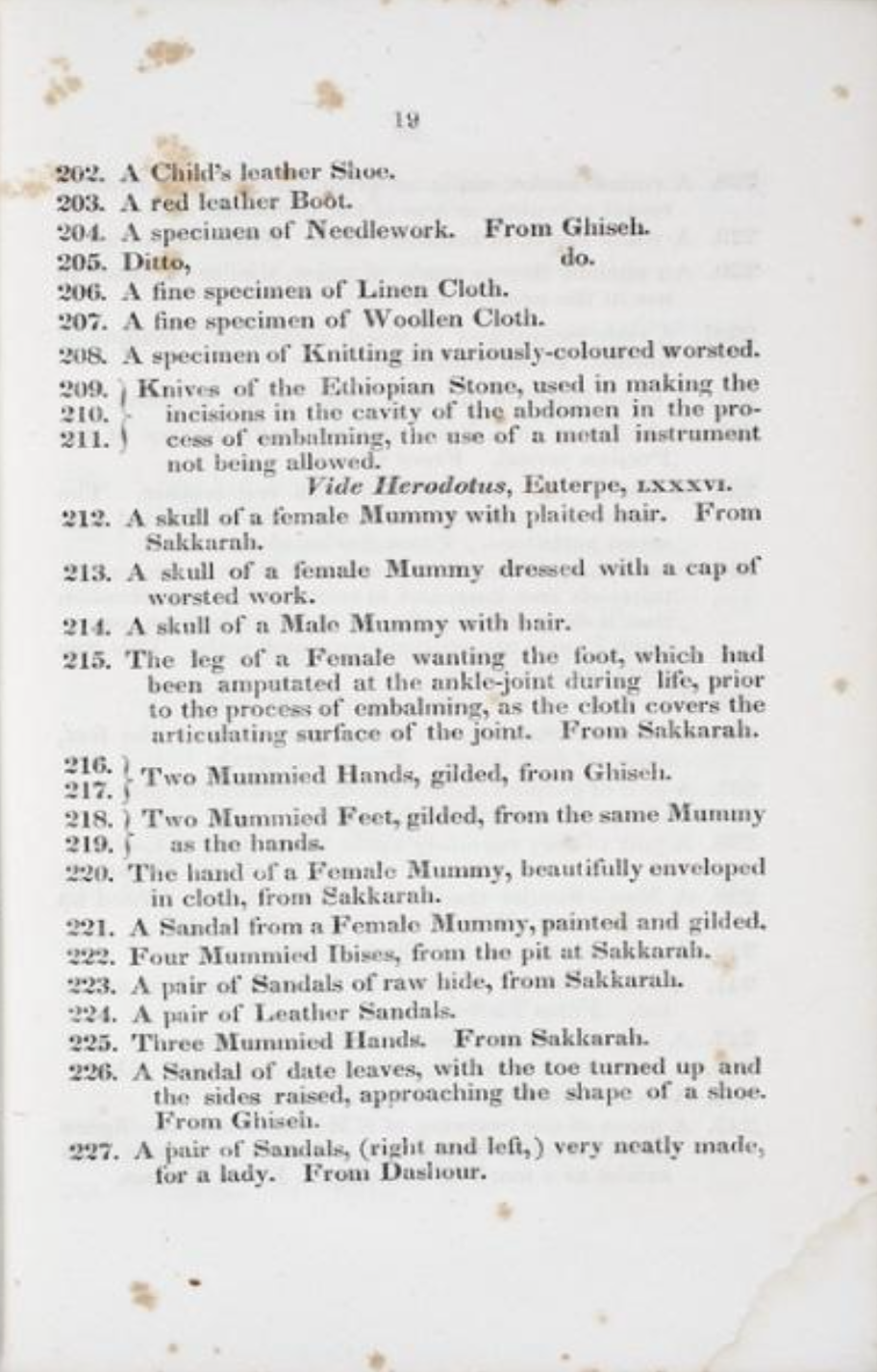

Listing of items from the Catalogue of Dr. Abbott's collection of Egyptian antiquities at Stuyvesant Institute New York New York T.B. Harrison 1854

One of the Lessons Bordering Broadway – The Egyptian Museum written by Whitman in 1855 for Life Illustrated is a quiet work. The subject is Dr. Henry Abbott's Egyptian Museum located on Broadway at the Stuyvesant Institute in New York during the years 1853-1860.

Dr. Henry Abbott was an Englishman who spent twenty years in Egypt collecting art and artifacts. He brought his treasured hoard to New York and Brooklyn (then a separate city) in 1853 in the hopes of selling the collection intact. When his attempts were unsuccessful he put the collection on public view at various locations including the Stuyvesant Institute at 659 Broadway where Whitman found it. Admission was 25 cents for this remarkable display; the first major exhibition of Egyptian artifacts in the United States.

In his role as journalist and newspaper reporter, Whitman frequently visited galleries and museums and reported on what he learned. He reportedly wrote over 1,200 pieces from 1842 to1848 alone. This was his most prolific period as a journalist but he had contributed to newspapers and periodicals before and after these dates. [5]

The visit is presented as a different kind of lesson – different from the kind of learning that springs from the sense experience of a walk through bustling streets. Whitman writes that “Many lessons are to be learned along Broadway, that great thoroughfare of New York…Some of these lessons are so plain that they who walk may read”.[6] This was an acknowledgement of the value of the life lessons to be found on Broadway through observation and accessible even to non-scholarly or semi-literate. Following this comment however Whitman steps away from the school of life and leaves the “gayest and most crowded” part of Broadway and enters into the “dim, dreary, silent and eloquent” halls of Abbott’s Museum. [7]

Although the atmosphere was hushed and the lighting low, the “visitor experience” at this time would have been quite different from that of a contemporary museum. Our knowledge of this first exhibition is based on published catalogs, on contemporary commentary, and on reactions from visitors via the Museum’s guest book, as well as writings by Whitman. It’s impossible to know how the objects were displayed, how many were on view at one time (the collection numbered over one thousand objects) or even the size of the space. Whitman describes his first look this way:

Around the walls of the room are slabs of limestone, some of them very large, each containing its spread of hieroglyphics. They are wonderful. They are as distinct as anything cut last week in New York or Boston. Now and then on the stones are portrayed snakes, fishes, pollywogs, toad, beetles and so forth…

Cover page of the Catalogue of Dr. Abbott's collection of Egyptian antiquities at Stuyvesant Institute New York New York T.B. Harrison 1854

There were also mummified cats, lizards, ibises, crocodiles and half unwrapped humans along with strips of papyrus, sandals boots knives spoons needles. The impression of disorder and anima mundi is confirmed by the catalogue with its plethora of objects loosely grouped – knives, knitting, mummified hands, a child’s leather shoe.

Whitman’s immediate impression was of an abundance of objects displayed according to the idiosyncratic sensibilities of the collector, Dr. Abbott, and infused with the ‘curiosity of the curator’. The arrangement suggests the wunderkammer model – with a dash of ‘Dime Museum’ sensationalism. This unlikely hybrid was the result of Abbott’s personal cabinet of curiosities’- originally on display at his home in Cairo transplanted complete to the bustling streets of 1850s New York, just down the street from P.T. Barnum’s American Museum.

In fact, the European model of museum exhibition display had not yet penetrated American shores. In an interview by Whitman for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle [8] with P.T. Barnum the contrast between the sensibilities of old world and the new was described by Barnum thusly: Why sir! You can’t imagine the difference – there everything is frozen – Kings and things – formal, but absolutely frozen. Here is life!

Although the character of Abbott’s collection was truly unique in many respects, it fit very well with the early nineteenth century American Museum tradition as exemplified by Barnum and begun by the man generally credited with founding the first American Museum, Charles Wilson Peale.

Peale’s American Museum opened to the public in Philadelphia on July 18, 1786. The objects exhibited included an 80 pound turnip, a chicken with two sets of wings and feet, and the preserved finger of a murderer. [9] After Peale’s death part of the collection was sold to P.T. Barnum and absorbed into his museum.

The European museum tradition of the same period was quite different, especially with respect to antiquity. One of the earliest English exhibitions “Belzoni’s Tomb” opened in London in 1821 and included many artifacts similar to those in the Abbott collection i.e. mummies and curiosities, but the exhibit was dominated by monumental and theatrical replications of the chambers of the tomb of Seti I which Belzoni announced he had discovered. The effect was intended to be an immersive experience at a static moment in time. This may have been influenced by Belzoni’s particular sensibility – he was a showman like Barnum but relied on different tactics, like the surprise of size and scale, to inspire awe. In Belzoni’s Belzoni's travels: narrative of the operations and recent discoveries in Egypt and Nubia, an account of his travels, he describes his own reactions to his discovery saying, “I was lost in a mass of colossal objects….a ‘forest’ of decorated columns: the gates, the walls, the pedestals…the high portals, seen at a distance from the openings to this vast labyrinth of edifices”. [10]

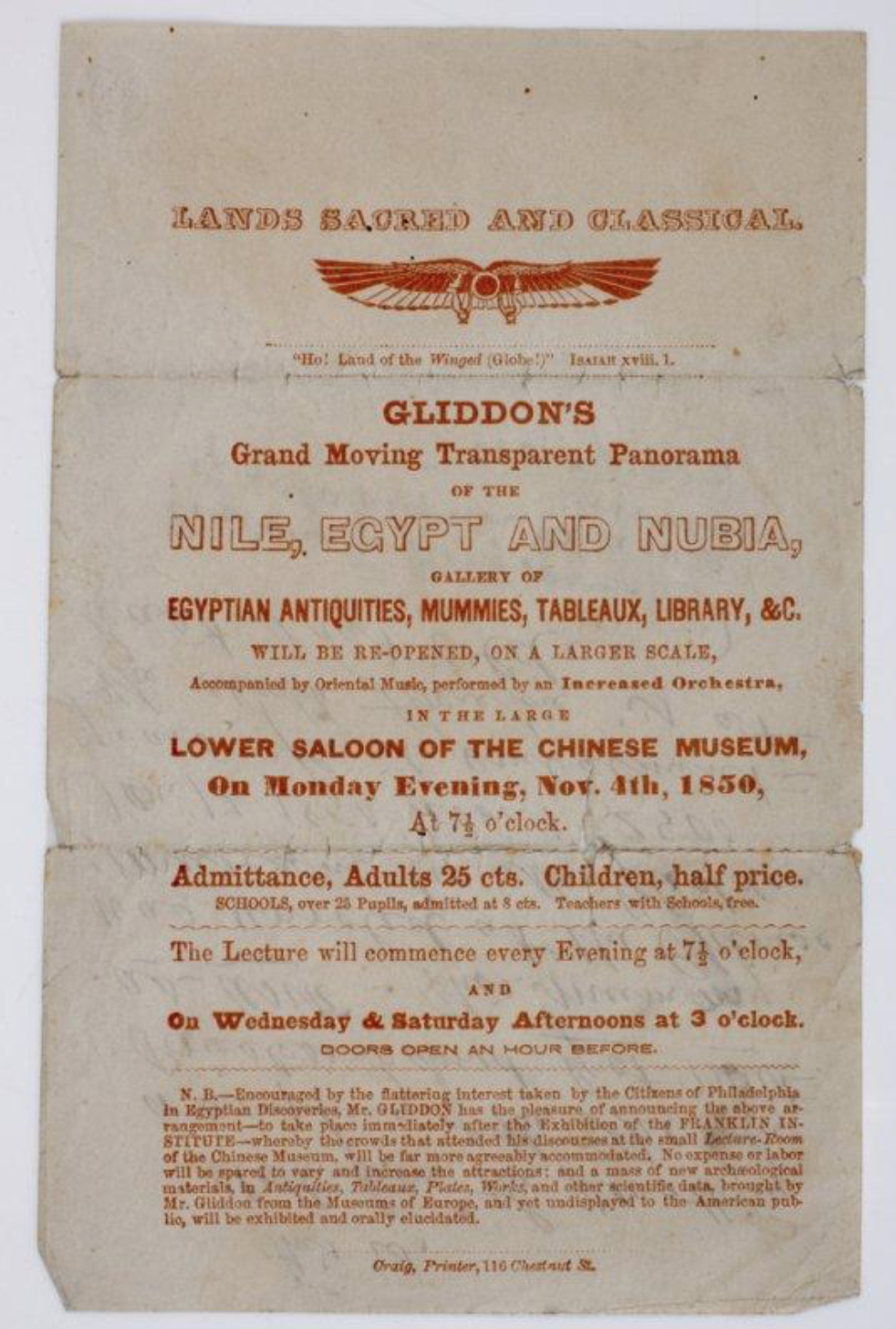

Handbill for Gliddon's Panorama of the Nile; November 4th 1850

Belzoni’s initial infatuation with monuments and mystery permeated his style of exhibition and influenced later European traditions of displaying Egypt. Abbott’s collection on the other hand, was created over time as a personal assemblage the objects were originally displayed in a domestic setting. The scale was human, eclectic and perhaps rather chaotic – a style that seems to have been preserved when the collection moved to New York.

Whitman was very familiar with museums like Barnum’s (located at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street) with its mixture of the odd and the educational. And Abbott’s museum, viewed through his eyes, inspired no distant reverence or awe. Whitman enters from the crowded street and immediately draws parallels between the ancient society and his own. There is no cyclopean forest of statuary and pillars - he imagines multitudes. In his words, the race that created these varied objects “existed in just as much vigor and reality and the United States exists today… in that country lived a population of many millions – there are good reasons to suppose them to be scores of millions.” He goes on to list, not only gods, but also markets, quays, barns, cattle, machines and amusements, the stuff of vivid daily life.

It’s not that Whitman was not knowledgeable or was dismissive of the scholarship on Egyptology of the time. He very respectfully mentions Wilkinson, Rossellini and Lepsius. He would also have been aware of some of the contemporaneous exhibitions and lectures on Egypt, such as George Gliddon’s Panorama of the Nile, which was performed in Brooklyn in 1849-1850 [11]. All wrote exquisitely on a past that was past. In contrast, Whitman could not seem to tear himself away from the present – his words are pure observation and experience.

By the time of Whitman’s visit Abbott had returned to Cairo and his museum to its fate. The collection was in danger of being sold off in parts or even discarded. Whitman’s essay itself is likely to have been part of a larger effort to convince a benefactor or institution to purchase the collection and keep it in New York. Whitman ends his piece by saying that such a collection ought never to be merely a transient exhibition….It is a museum to have permanently in some great, free. Learned institution…these relics of the real life of a mighty and long dead nation are hardly fit subjects for a twenty-five cent show. [12]This last is puzzling and further supports an ulterior motive on Whitman’s part. He had seldom before disparaged the exuberant chaos of the dime museums of Broadway or the promiscuous mix of high and low culture in the city’s cultural attractions.

Mummified Apis Bull on display the New York Historical Society (pre-1937) – New York Historical Society Image 85440d.

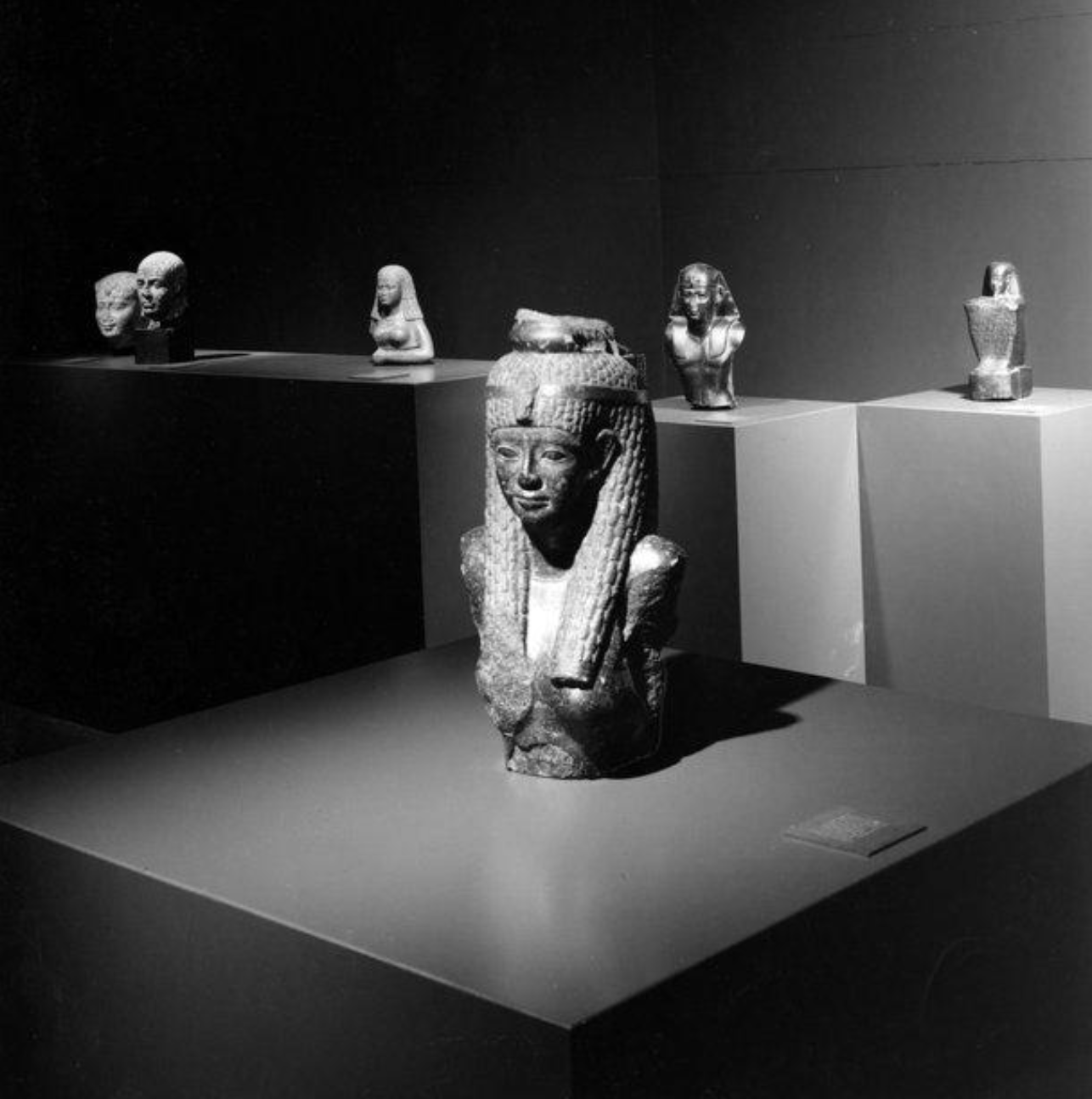

In time, order would be imposed on Dr. Abbott’s idiosyncratic hoard. The collection, which had been offered as a whole to several institutions including the British Museum (which declined to purchase it), was put on deposit at the New York-Historical Society in 1860 after lengthy public discussion about the need for a serious exhibition of Egyptian antiquities in America for the benefit of the public. In its presentation of the Abbott collection the Society attempted to preserve both the collector’s vision and the acquisition history, while emphasizing the aesthetic aspects the collection. It was catalogued by the Egyptologist and classical archaeologist Caroline Ransom Williams and was displayed with rather more order than before in the museum of the New York Historical Society.

In 1937 the collection was placed at the Brooklyn Museum on loan from the New York Historical Society. The terms of the loan agreement required that the collection be displayed as a separate unit. In 1948 the Abbott collection was purchased by Brooklyn at which point it was fully integrated into the Museum’s existing Egyptian and classical art collections and ceased to have a separate identity. The curator of Egyptian Art John D. Cooney dismissed the collection’s aesthetic value as merely “A record of 19th century taste in collecting”. Abbott’s vision as a collector was likewise discounted as minor.

Whitman’s impressions of Abbott’s Museum are one of the few records we have of the way this collection was viewed in its time; of the way of it travelled and evolved. His words are part of the Abbott collection’s living history where:

Egyptian Gallery Brooklyn Museum c. 1960s Brooklyn Museum Archives

Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined

The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from

What has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands

Then again on their feet…he says to the past, Rise and walk before

Me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson…he places himself

Where the future becomes present. [13]

+++

[1] A Broadway Pageant; Leaves of Grass (1881-1882)

[2] Broadway, the Magnificent; Life Illustrated November 8. 1856.

[3] A Broadway Pageant; Leaves of Grass (1881-1882)

[4] Broadway; Written for the Herald April 10, 1888 New York Herald

[5] For more information on Whitman’s journalistic reporting see the Walt Whitman Archive: Published Works: https://whitmanarchive.org/published/periodical/journalism/index.html

[6] One of the Lessons Bordering Broadway: The Egyptian Museum; Written for Life Illustrated 1855

[7] Ibid

[8] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, , May 25, 1846

[9] Hudson, K. (1975) A Social History of Museums: What the Visitors Saw. London Macmillan

[10] Belzoni's travels: narrative of the operations and recent discoveries in Egypt and Nubia Brussels: H. Remy, printer, 1835.

[11] Advertisements appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle throughout 1849 and into early 1850. The Panorama itself was a painted scroll which wound and unwound on rollers and was lighted from behind. The whole thing was set to music and some performances included a mummy-unwrapping.

[12] One of the Lessons Bordering Broadway: The Egyptian Museum; Written for Life Illustrated 1855

[13] Walt Whitman; Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass